Indigenous Peoples in Colombia represent 4.4 percent of the total population.1 In the Amazonas department, they make up 57.7 percent of the population and they have experienced the highest COVID-19 infection and mortality rates in the country.2 Due to the existing conditions of Indigenous Peoples in Colombia, they are particularly vulnerable to the pandemic, including to some of the measures the government has imposed to address the health crisis. As with the case of Omar and Ernesto Guasiruma of the Indigenous Emberá Peoples, they were murdered at their home while following the quarantine order.3

In 2020, there were a total of 310 killings of human rights defenders and social leaders; 113 of them were indigenous.4 Furthermore, there were 94 documented incidents of mass displacement due to violence with 76 percent of these occurring in Antioquio, Chocó and Nariño. The latter two departments are home to a number of indigenous communities, affecting 25,366 people.5

Although viewed by the Colombian state as a failed development model, the Indigenous Peoples’ collective way of life has proven to be more effective in supporting their existence and persistence of their culture.6 It poses a challenge to the state’s current development model, which is extractive and unsustainable and is characterized by privatization. Because of this, Indigenous Peoples are subject to attacks and harassment from the state, corporations, armed groups and other powerful actors who aim to seize their lands, territories and natural resources for profit. This directly impacts on their ability to exercise their self-determination, autonomy and self-government.

Also, despite the Ministry of Defense’s issuance of a policy of zero tolerance to sexual violence, there had been three cases documented within the year involving members of the police and the military. Two of them involve indigenous girls.7 Rape of indigenous girls in Colombia is more common than is reported,8 that from 2016 to July 2020, around 118 soldiers were investigated for alleged cases of sexual abuse against minors.9

Ongoing institutional reforms may exacerbate the impunity against Indigenous Peoples and their vulnerability to attacks and violence.10 Among these reforms are the weakening of the Ombudsman’s Office, the institutional capture of the Office of the Attorney General of the Nation, attempts to weaken the State’s duty to consult,11 and ignoring national jurisprudence and the international obligations of Colombia.

For many Indigenous Peoples all over the country, the Peace Agreement signed in 201612 has not brought peace to their lives and territories. Violations of their rights persist in a climate of near total impunity. The continuation of historical forms of violence are now coupled with increased stigmatization, hate speech, attacks against organizational structures, incitement of inter- and intra-ethnic conflicts, and criminalization. Although these recent strategies are non-lethal, they are proving to be effective in reducing the autonomy, self-government and the collective capacity of Indigenous Peoples to defend their lands and territories.

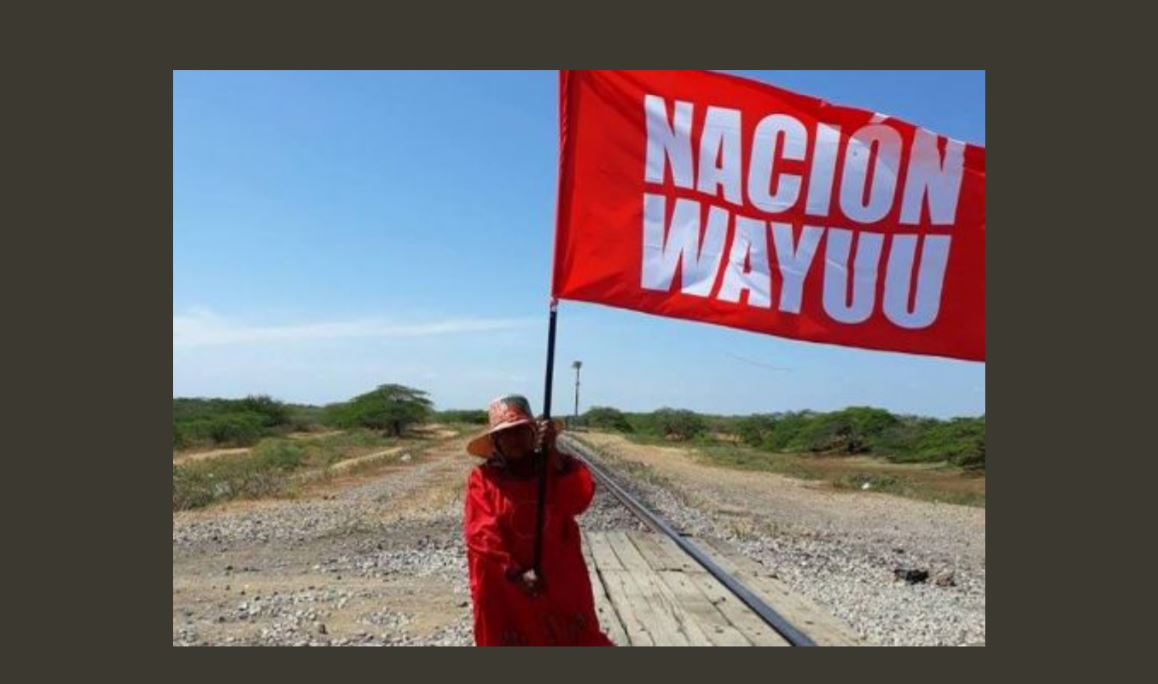

EL CERREJÓN COAL MINE OPERATES WITH GOVERNMENT’S SUPPORT IN SPITE OF THE DEADLY IMPACTS ON WAYÚU TERRITORIES AND RAPE THREATS AGAINST INDIGENOUS WOMEN WAYÚU LEADERS

Jakeline Romero is a Wayúu leader of the Fuerza de Mujeres Wayúu (Sütsüin Jiyeyu Wayúu) at the Wayúu Indigenous Reserve of Zahino in La Guajira. She has endured countless death threats and harassments over the years of protesting against Cerrejón coal mine operations and demanding redress for damages. As with other women activists from indigenous and local Afro-descendant communities, Romero has received threats of rape and death against her family members.13 Perhaps the most alarming is a written message sent to her home in 2016 stating, “Your daughters are very beautiful, think about them and stay out of trouble, I will disappear even your mother if you continue to snitch.”14 It was the first time she received a threat directed at her loved ones.

The Cerrejón coal mine, operating in La Guajira since 1976, is a U.K. – Swiss – Australian conglomerate of BHP, Glencore and Anglo-American.15 Its decades of operation and expansion have completely devastated, if not wiped off, a number of communities like Roche, Chancleta, Tamaquitos, Manantial, Tabaco, Palmarito, El Descanso, Caracoli, Zarahita, and Patilla. The mine spans 69,000 hectares of land in the middle of the Indigenous Wayúu territory and has heavily polluted the water source until it completely dried up. The El Cerrado dam project that was meant to address the lack of water in the nine municipalities of La Guajira ended up serving Cerrejón mine and farms owned by private companies.16

The Wayúu and other Indigenous Peoples thought they could safely reclaim their territories after the signing of the Peace Agreement in 2016, but development aggressors like the Cerrejón coal mine remain a threat to their claim of rights to their lands and territories.

In September 2020, UN experts issued a statement calling for Cerrejón mine to cease operations. They noted how the State of Colombia and owners of the El Cerrejón ignored the Court order issued in December 2019.17 David Boyd, UN Special Rapporteur on human rights and the environment said, “Colombia [should] implement the directives of its own Constitutional Court and to do more to protect the very vulnerable Wayúu community on the Provincial indigenous reserve against pollution from the huge El Cerrejón mine and from COVID-19.”

Without government support, the Wayúu people are left with no choice but to live with the coal dust and the drought. They face severe malnutrition due to lack of water and access to basic health care.18 Death among children and elders due to poor air quality coupled with contaminated water and vegetation is common.

The Colombian government and Cerrejón owners have to be held accountable for the violations of the Wayúu peoples’ rights to their lands and resources, life and dignity in La Guajira.

VIOLENCE AND ATTACKS CONTINUE AGAINST THE EMBERÁ CHAMÍ PEOPLE IN CAÑAMOMO – LOMAPRIETA INDIGENOUS RESGUARDO

The historic Resguardo of Cañamomo Lomaprieta, located within the jurisdiction of the municipalities of Riosucio and Supía, department of Caldas, is the home of 23,000 Emberá Chamí inhabitants. The Resguardo is 4,836 hectares, which is insufficient for the current population. According to estimations in the country that consider the ratio of minimum land area per person, the Emberá Chamí in Cañamomo Lomaprieta has a land deficit of 80 percent.

The Emberá Chamí people in Cañamomo Lomaprieta have suffered from historical and continuing dispossession of their territory and resources, and they are subject to violence and attacks due to their defense of their land rights. From 2000 to 2015, Cañamomo Lomaprieta and the surrounding Emberá Chamí Resguardos particularly consider the massacres of La Rueda in 2001 and La Herradura in 2003, and the murder of María Fabiola Largo Cano19 and Fernando Salazar Calvo20 in 2002 and 2015, respectively, as having indelible impacts on their individual and collective rights. The victims of these series of gross human rights violations were traditional authorities and political leaders who posed a serious challenge to the local political elites who also have links to para-militarism.

Both the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) and the Colombian Constitutional Court have recognized the high-risk situation of the Resguardo. The IACHR granted precautionary measures in 2003, while the Colombian Constitutional Court included the Emberá Chamí among the Indigenous Peoples at risk of ‘physical and cultural extinction.’21 In 2016, decision T 530/2016 of the Constitutional Court ordered the National Land Agency to advance the process of titling and securing indigenous lands in the Resguardo.22There has been no progress in the implementation of the decision, while both illegal mining and privatization of collective lands continue. Moreover, these court decisions, which are consistent with Colombian Constitutional provisions, legislation and international standards on Indigenous Peoples’ rights have resulted in the escalation of violence against the Emberá Chamí, as different actors interested in their lands and natural resources are redoubling their efforts to control the Resguardo.

Furthermore, in 2019, Senator Carlos Felipe Mejía introduced House Bill 354/2019, which intended to establish an ad hoc commission to advance the restructuring of the Cañamomo – Lomaprieta Indigenous Reservation, ignoring the Constitutional Court’s decision. This action was accompanied by media campaigns stigmatizing and accusing indigenous authorities of colluding with illegal armed groups, resulting in a new wave of attacks.

On March 20, 2020, the Office of the Ombudsman activated the Early Warning System23 over the situation in the Cañamomo – Lomaprieta Indigenous Reservation. The EWS activation triggered several violent acts against community property within the month of March. From March 6 to 17, farms and community sugar mills, which were the main source of livelihood for around 90 Emberá Chamí families were set on fire on four different occasions. The attacks may have led to forced displacement and compromise the safety and security of their leaders and their way of life.

After the first two attacks, a Security Council meeting was held with the National Army, National Police, carabineros, the Mayor’s office, the Cuerpo Técnico de Investigaciones (CTI) de la Fiscalía, and indigenous authorities on March 8. State authorities promised investigation of the incidents, and prevention and protection from any future attacks. On the same day, armed men approached an indigenous leader and warned him to leave the territory.* That evening, the third attack happened. Death threats sent via WhatsApp, claiming to be either from the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia / Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) or the National Liberation Army / Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN) were also received by community members.

On August 28, 2020, pamphlets were disseminated indicating that several members of the Indigenous Governing Council and the Indigenous Guard were collaborating with FARC guerillas, making them targets of the National Military.

Fear and insecurity remain high in the Resguardo.

Read and download the full IPRI's 2021 Annual Criminalization report here.

%2020.49.20.png)